College of Human Sciences

Weighing in on the 2017 Kenyan elections

The WIPHOLD-Brigalia Bam Chair in Electoral Democracy in Africa, in partnership with the Institute for African Renaissance Studies (IARS) and the Institute for Dispute Resolution in Africa (IDRA) at Unisa, hosted a seminar last week on the outcomes of the 2017 Kenyan elections.

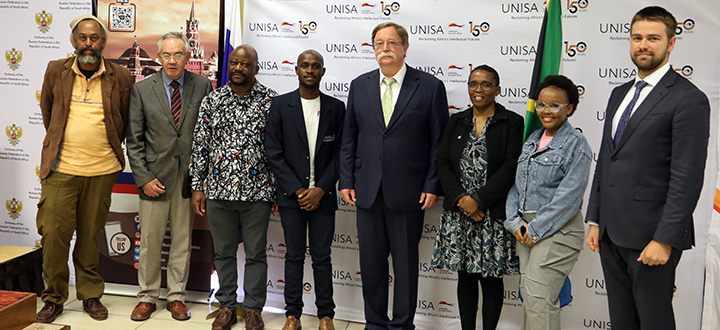

Pictured at the seminar: Advocate Sipho Mantula (Researcher: Institute for Dispute Resolution in Africa), Prof Kealeboga Maphunye (Incumbent: WIPHOLD-Brigalia Bam Chair in Electoral Democracy in Africa), Vhulenda Mukheli (Department of Political Sciences, Unisa), and Dr Martin R Rupiya (Associate Professor, IARS).

Three speakers, Prof Kealeboga Maphunye, incumbent of the WIPHOLD-Brigalia Bam Chair in Electoral Democracy in Africa, Advocate Sipho Mantula, Researcher: Institute for Dispute Resolution in Africa, and Dr Martin R Rupiya, Associate Professor, Institute for African Renaissance Studies, examined the context, developments and outcome of the now disputed Kenyan Presidential election results of 8 August 2017 that was brought before the Supreme Court in Nairobi on 1 September 2017.

In the presenters’ views, the state re-construction project in Kenya since the introduction of multiparty democracy continues to be work in progress with the unfortunate trend of consolidating ethnic and sub-regional tendencies and impressions of the now heavily contested notion of “only the Kalenjin and Kikuyu” representing 12 and 22% of the population groups in the country, respectively. Other population groups are now saying, “enough is enough” even where they do not have the popular vote, suggesting that the environment may be ripe for deliberate power sharing as a conflict prevention strategy. Overall, however, there are many dynamics at play when one analyses the situation in Kenya. These dynamics have fundamental historical, political, socio-cultural and other ramifications that affected the 2017 elections; making Kenya an exciting African case study in terms of elections, democratisation, governance, and the roles of dispute resolution, the judiciary and the security apparatus in the country’s politics.

Prof Kealeboga Maphunye (Incumbent: WIPHOLD-Brigalia Bam Chair in Electoral Democracy in Africa).

On Tuesday 8 August 2017, in line with the Constitution and the country’s Elections Act, Kenya held its National General Elections to elect the President and Vice-President, County Governors and Vice-Governors; Members of the Senate; Members of the National Assembly; Women County Representatives to the National Assembly in the 47 Counties; and Ward County Representatives to the National Assembly, which were organised by the Independent Electoral & Boundaries Commission (IEBC). Since the advent of multiparty democracy and the introduction of competitive elections as the route for political succession in 1992, Kenya’s plebiscites have been characterised by violence and allegations of rigged elections. The massacres that occurred in 2007 which had left just over 1 100 people killed—largely by machetes, with nearly 650 000 internally displaced—cast a dark shadow on the 2017 elections. Significantly, the profile of the victims reflected ethnic and sub-regional dimensions affecting the Luo in the Western region around Kisumu and the slum areas of Kibera and Mathare in the capital, Nairobi. President Kenyatta and his alliance partners had been implicated in the fast moving pogrom and had been indicted to appear before the International Criminal Court (ICC) based in The Hague. All these developments underscored the political context of the August 2017 national elections, which became a high stakes, tension-filled electoral event that was significantly characterised by undue influence of money, party politicised biased media coverage and allegations of rampant vote-buying.

In the run up to the 2017 elections, major reforms were undertaken towards strengthening the judiciary, the IEBC and its information technology (IT) division that had brought on board a Canadian IT company to work with the Election Commission in order to enhance its perception of transparency and integrity in the eyes of the public and the opposition political parties. These parties were under the umbrella organisation of the National Super Alliance (NASA) led by indefatigable Raila Odinga; whilst President Uhuru Kenyatta led the incumbent Jubilee Party of Kenya. Subsequently, the Commissioners of the IEBC were forced to resign with a fresh team put into place following spirited public marches against its composition and the perceived bias of its Chairperson in the run up to the August poll. The same was true of the improved legislative and judicial instruments put into place as part of safeguarding against stolen elections.

As if to herald a difficult election, eleven days before polling, the IEBC’s Head of Information, Communication and Technology, Christopher Musando was murdered in gruesome and suspicious circumstances after executing the developing and adoption of a new voting system, the Kenya Integrated Elections Management System (KIEMS). Initially, there were some insinuations that this death was related to adultery (given that the deceased was married but his corpse was found closer to that of an alleged lover), but his death was also ascribed to the machinations of the ruling party’s attempts to hang onto power. Undoubtedly, this development cast a dark cloud of suspicion on the integrity of the vote that was to be managed using the IEBC’s KIEMS gadgets. Furthermore, reports, later confirmed by government officials, indicated that the military establishment had conceptualised Operation Dumisha Utivulu—against the possible defeat of the incumbent and the opposition supporters breaking into riots. On this, a unit comprising 226 well-armed and mobile unit was allegedly established in the Mariakana Barracks.

Outcomes

Within a few hours of the poll ending, the computer-generated information began to reflect a commanding lead for the incumbent. In the end, Uhuru Kenyatta of Jubilee secured 8 203 290 or 54% of the vote against the main losing candidate, Raila Odinga’s 6 762 334 or 44.7% of the poll. Before end of seven days, late afternoon on 14 August, Raila Omolo Odinga and his running mate, Stephen Kalonzo Musyoka filed a petition challenging the announcement by the IEBC declaring Kenyatta the Presidential winner; and alleging that the “IEBC systems were hacked” and accusing the IEBC for flouting parts of the Elections Act and the country’s Constitution.

This is the third time in a row that Odinga has cried foul after claiming that he was cheated out of rightful victories in 2007 and 2013. The disputed 2007 election led to politically motivated ethnic violence and in 2013 Odinga took his grievances to court but lost. This time around in 2017, the main grounds of his petition were that some of the presidential results were derived from non-existent polling stations by ungazetted presiding or returning officers. Odinga also claimed that the results that declared Kenyatta the winner were not submitted procedurally.

The legal wisdom and analysis that took place for fourteen (14) days and composed of forty (40) supported senior legal officials and seven (7) Supreme Court of Appeal judges had to dissect around fifty and seventy thousands (50 000—70 000) pages of evidence submitted by both parties (70 000) and to deliver the judgment on the 1 September 2017.

Before the petition could be heard by Kenya’s Supreme Court on 1 September 2017, there were two most likely judicial scenarios of a ruling which was conducted for eleven days. The first was the likelihood of a second presidential vote should the court rule in favour of the petition. In terms of Kenya’s Constitution, the second vote would be held within 60 days after the ruling, or on Wednesday 1 November 2017. The second scenario would be the swearing in of a re-elected President Uhuru Kenyatta on Tuesday 12 September 2017, should the court dismiss the NASA petition.

In a historical judgement that enhanced the integrity and independence of the judiciary in Kenya, the Supreme Court on 1 September 2017 nullified the results of the Presidential Election and ordered a re-run. This decision, which must have brought temporary relief to many Kenyans who had feared the possible outbreak of violence that would follow the court’s ruling, suggested the entrenchment of the principle of the separation of powers in Kenyan politics and highlighted the judiciary’s critical role in the country’s democracy.

Nevertheless, the political crisis in Kenya has deep-seated contradictions related to ethnic hegemony and marginalisation of some ethnic groups, unfulfilled promises around poverty reduction, youth unemployment, unresolved land issues, social inequalities, heavy-handed police and security action against constitutionally sanctioned rights to free political expression and movement; and lastly, the role of the IEBC as defined by Kenya’s Constitution and the country’s Elections Act. The big question remains whether the Supreme Court’s decision that ordered a re-run of the presidential elections will effectively resolve all these contradictions. Inevitably, however, the Kenyan situation also has to be examined within the context of the African Union’s Charter on Democracy (2007), and AU Principles and Guidelines Governing Democratic Elections (2002).

In conclusion, what happened at the Supreme Court of Kenya on 1 September 2017, was a historical milestone not only for Kenya but for East Africa and the African continent in terms of Africa’s attempts at democratic consolidation. Indeed, the court’s decision will have far-reaching implications for the integrity of elections as a means for choosing and removing leaders in Africa’s in its quest for democratisation.

*By Kealeboga Maphunye, Sipho Mantula, and Martin R Rupiya

Publish date: 2017-09-04 00:00:00.0

Unisa's student leadership engage with Russian ambassador

Unisa's student leadership engage with Russian ambassador

Re-igniting and re-imagining Pan Africanism, Afrocentricity and Afrofuturism in the 21st century

Re-igniting and re-imagining Pan Africanism, Afrocentricity and Afrofuturism in the 21st century

Young Unisa science stars join elite Lindau Nobel Laureate group

Young Unisa science stars join elite Lindau Nobel Laureate group

Education MEC addresses Unisa autism seminar

Education MEC addresses Unisa autism seminar

Seven Unisans nominated for the NSTF-South32 Awards 2023/2024

Seven Unisans nominated for the NSTF-South32 Awards 2023/2024