The largest provider of business education in Africa and one of the largest in the world

While the country is obsessed about the South African Reserve Bank (SARB) and monetary policy as the only answer to our growth problems, we will fail to discuss the difficult but vital reforms that might actually rescue us from our growth malaise, said Reserve Bank Governor Lesetja Kganyago at a Unisa public lecture.

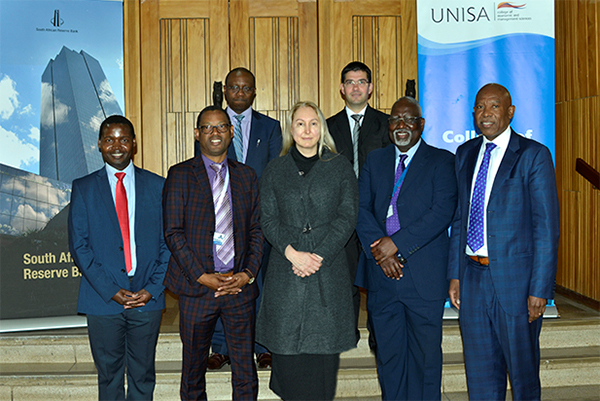

Almost 300 attendees from the diplomatic corps, business, government, non-government organisations, the media and trade unions, as well as Unisa staff and students, packed the Senate Hall for the second public lecture hosted by the College of Economic and Management Sciences (CEMS).

Reserve Bank Governor, Lesetja Kganyago

"This 'obsession', as Mr Tito Mboweni, the Minister of Finance calls it, is getting in the way of a more fundamental discussion about economic growth, job creation and dealing with inequality," said Kganyago. "The growth problem in South Africa is mainly structural in nature and beyond the reach of monetary policy alone and the growth effects of a rate cut are small. Critics will say we could have cut rates to get higher growth, but South Africa’s growth problem is caused mainly by structural problems like a constrained electricity system as well as policy uncertainty. Given these constraints, a monetary policy that tolerated higher inflation for the sake of more demand would have yielded, at most, relatively small and temporary benefits, at the price of long-term costs."

According to Kganyago, the SARB has modelled what would happen if the monetary policy committee (MPC) start aiming for a 6% target again. "If we cut rates by about 100 basis points, growth would be half a percentage point higher, at its peak, and about a third of a percentage point higher the year after that. That isn’t much growth, and certainly not a game-changing growth recovery," he said. "The effect of tolerating more inflation over the shorter term (one or two years) can allow a looser stance, but this effect is temporary."

Kganyago explained to the students in the audience that by the time they graduate and go to work, they are going to face higher interest rates. Their student loan repayments will be higher. A car payment will be more difficult. A mortgage will be costlier. "All this will have real implications for your incomes," he said.

Front, from left: Prof Christopher Mulaudzi (Acting Deputy Executive Dean: CEMS), Prof Khehla Ndlovu (Vice-Principal: Strategy, Risk and Advisory Services, Unisa), Annabel Bishop (Chief Economist at Investec Bank), Prof Thomas Mogale (Executive Dean: CEMS), Lesetja Kganyago (Governor of the SARB); back from left: Dr Montfort Mlachila (Senior Resident Representative of the International Monetary Fund in South Africa) and Fanie Joubert (Senior Lecturer in Economics at Unisa).

He warned that South Africa doesn’t have balanced and sustainable growth. "With annual GDP growth rates under 1%, there is barely any growth," he said. "Adjusting for the increase in the population, South Africans have been getting poorer for half a decade. At the same time government’s debt-to-GDP ratio is moving steadily higher, and with bailouts for state-owned enterprises, there are real risks that the country will soon have one of the highest debt levels amongst its emerging market peers. Because of overseas borrowing, a rapidly rising amount of interest is being paid to non-South African creditors. This is contributing to a large current account deficit – again, one of the biggest in our peer group."

Kganyago said that failing to get the conversation about growth going, feeds the notion that the SARB’s private shareholding matters to the existing policy framework and the decisions made on policy. "The shareholding debate is more damaging to the economy than it should be," he said. "It sends a signal to investors, both here and abroad, that our macroeconomic framework is at risk, making the cost of debt higher than otherwise and undermining confidence. Those who lose the most are indebted households and the beneficiaries of public spending, who pay the price for skyrocketing interest costs on our public debt as the resources to spend are squeezed."

There are real limits on what monetary policy can do to help as there is no monetary policy stance that would single-handedly transform South Africa’s prospects, he emphasised.

He said he was worried that as economic circumstances get increasingly difficult, more people will choose to avoid making hard choices and pretend they do not need to be made, as if the SARB could just cut rates enough and all will be well. The SARB can deliver low and stable inflation. But balanced and sustainable growth also requires contributions from many other parts of government and society. The country needs to maintain prudent macroeconomic policies and has to make further progress on a range of structural issues.

"Ultimately, prosperity cannot be created by an MPC setting interest rates. We are but one part of the orchestra; we are not soloists. We are doing our best but we can’t put on a show alone," he said.

The objective of the CEMS public lectures is to contribute to the national debate on issues of importance and at the same time, ensure that a wide range of opinions are heard and debated. The third public lecture in the 2019 series will be hosted by the college later in the year.

* By Ilze Crous, Communication and Marketing Specialist, College of Economic and Management Sciences

Publish date: 2019-07-28 00:00:00.0