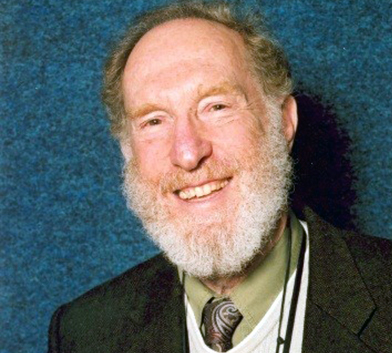

Reaching the top is one thing; staying there is quite another. Unisa Professor Extraordinarius, David Glasser, is in a class of his own, with four consecutive A1 ratings from the National Research Foundation.

Reaching the top is one thing; staying there is quite another. Unisa Professor Extraordinarius, David Glasser, is in a class of his own, with four consecutive A1 ratings from the National Research Foundation.

“I don’t do the work for the sake of an A1 rating—that’s a nice-to-have. I do the work because I love it,” says Glasser, a retired professor of chemical engineering, who this year received his fourth A1 rating since 1998. “For me, science is all about the Ps—passion, patience, perseverance, and persuasion. You have to love what you do.”

Clearly he thrives on his work with Unisa’s Material and Process Synthesis (MaPS) unit—which he does from a distance. Sydney in Australia has been his home since the end of 2015, when he and his wife Sylvia moved there to be with their daughter and granddaughters.

“With modern electronic communication, you don’t need to be sitting in the same room,” says Glasser, who retains his association with Unisa through his role as Professor Extraordinarius, a rare, non-tenured position for scholars who have achieved academic excellence and are recognised as global leaders in their fields.

Glasser is internationally known for his work on chemical process optimisation, catalysis and synthesis, among others, but jokes that the global leader in the family is actually his wife, Sylvia, an acclaimed dancer and dancing teacher. “She is more famous than I am,” he says, referring to the knighthood Sylvia received from the Dutch government and the Order of Ikhamanga, Silver, awarded to her by President Jacob Zuma in 2016.

Still, Glasser himself has his fair share of awards. Over and above his A1 ratings, he is a recipient of the Gold Medal of the SA Institution of Chemical Engineering for his research work, as well as the inaugural Harry Oppenheimer Gold Medal and Fellowship and the Science for Society Gold Medal from the Academy of Sciences of South Africa.

A former Dean of the Faculty of Engineering at Wits University, where he spent 48 years, Glasser joined Unisa in 2013. Together, he and Professor Diane Hildebrandt, also previously from Wits, established MaPS, which has been doing some ground-breaking research in waste-to-energy conversion, the optimisation of chemical reactors and devising a new method to make chemical plants more efficient (e.g. less carbon dioxide emissions).

They continue to work closely, despite being on different continents. “Unisa is, of course, a distance learning institution! As I said, you don’t need to be in the same place to collaborate; you just have to be of one mind,” says Glasser. “We are both trying to find the truth. We are not frightened of making mistakes and we are not antagonistic towards people who tell us we are making mistakes.”

Indeed, one of Glasser’s worst “mistakes” turned out to be a boon for Hildebrandt. “After my PhD, I had an idea for optimising chemical reactors that I pursued for 15 years. When I eventually got to a solution, it was totally useless—but it became the inspiration for Diane’s PhD. The biggest mistake is not necessarily the biggest mistake if you learn from it.”

Another quality he values is teamwork. “There are researchers who want to share and those who don’t want to share. I like to work in a team and throw ideas around. Ideas come from the interaction between people.”

An example is the book that he, Hildebrandt and other authors from South Africa and the United States have just authored, titled Attainable Region Theory: An introduction to choosing an optimal reactor (Wiley USA 2016). “There are many authors because we don’t sit down and say, ‘Whose idea is that?’ If you can be an Einstein and work everything out yourself, then that’s fine. I prefer to be part of a team.”

One trend among universities that he is less optimistic about is the increasing drive to manage research. “Universities think they are helping by trying to manage research but all they are doing is making more work for researchers and stifling their creativity,” Glasser says. “The purpose of the administration should be to hire the best people and give them as many opportunities as they can to fulfil their potential. You’ve got to have confidence in the people you hire and leave it to them to follow their instincts and do the job.”

That approach has certainly worked for Glasser, whose 51-year career has produced about 200 papers and three books, with a fourth book in progress.

Asked what legacy he would like to leave, he says: “I don’t want to make a mark. I hope the work will make a mark but that’s not why I do it. I love what I do, even when things go wrong—and they will go wrong. Nobody is that clever to get it right all the time. And if things come too easily, we don’t learn. We only learn from our mistakes.”

*By Clairwyn van der Merwe

Publish date: 2017-06-23 00:00:00.0

National leader in mathematics education aims to improve outcomes

National leader in mathematics education aims to improve outcomes

Unisa roundtable focuses on empowering SA women to lead in innovation

Unisa roundtable focuses on empowering SA women to lead in innovation

Unisan recognised for web excellence

Unisan recognised for web excellence

Office of the Dean of Students participates in leadership camp

Office of the Dean of Students participates in leadership camp

Unisa project fosters digital and pedagogical innovation in Limpopo schools

Unisa project fosters digital and pedagogical innovation in Limpopo schools