College of Human Sciences

CHS CE project on climate change and its links to Covid-19

Community engagement (CE) in the College of Human Sciences has not come to a halt in spite of the coronavirus pandemic. In fact, for scholars such as Prof Monika dos Santos from the Department of Psychology, it is all systems go for her climate change healthcare adaptation project.

She chatted to the news team on the Climate change adaptation: Community healthcare and systems strengthening project in Kruger to Canyons Biosphere.

Please tell us about your project: When it started, what it is about, who is involved?

The concept for the project, namely focusing on climate change and health impacts within the South African and African context, first came to my mind when I was working as a Technical Advisor at the Foundation for Professional Development, a private institution of higher education affiliated to the South African Medical Association. I viewed a random National Geographic DVD lying around at the home of relatives of mine called Six degrees can change the world (who knows how the DVD got there). It was convincing and a real eye-opener. I was instantly drawn to the field of climate change. Little did I know then that it would take me to all corners of the world and South Africa, including the Massachusetts Institute of Technology Centre (MIT), the universities of Oxford and Paris-Sorbonne, and, soon to come, Guyana and the Amazonian basin (and I’ve heard this expedition is not for the faint hearted).

I ran my concept and thoughts by Saul Kornik, who was then the CEO of Africa Health Placements, and soon afterwards I submitted an outline to MIT for Collective Intelligence Climate CoLab initiative, and the concept was awarded formal recognition by MIT. By then I had started working at Unisa, and registered it as a community engagement project to be piloted in the Kruger to Canyons Biosphere Region, initially in collaboration with Africa Health Placements.

Prof Monika dos Santos (Department of Psychology, CHS, Unisa) (right) is the conceptualiser and leader of the Climate change adaptation: Community healthcare and systems strengthening project in Kruger to Canyons Biosphere. Here she is pictured chatting to a colleague at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, USA, in December 2013, when she presented the concept for the first time.

Photo credit: MIT

Why is your project important and how is it helping the community?

The project is essentially a systems-strengthening initiative aimed at providing a solid evidence base in order to make a case for programmatic interventions. Initially, the medical field simply did not take climate change seriously. This is starting to change, though, and I hope we have played a role in that. We have also conducted workforce assessments of most of the public healthcare facilities in Agincourt, Bushbuckridge Municipality.

In addition, as a direct result of this project, we were awarded a national Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) grant last year to conduct a risk and vulnerability scoping project commissioned by the national Department of Health and the Department of Environment, Forestry and Fisheries. By partnering with the Council for Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR) and Africa Health Placements, as well as experts in France and the Netherlands, we drafted South Africa’s first National Risk and Vulnerability Assessment (RVA) framework for climate change and health - a difficult task to undertake, but a fruitful one, owing to its originality, scarcity of resources and uncertainty involved.

In many ways, the Covid-19 pandemic has confirmed that a nested public health approach is necessary in order to conduct large-scale public health interventions. One needs to look at a global, national, district, and at a local facility level in terms of infrastructure and capacity - we have seen only too grimly the lack of beds and mortuary space in Spain, for example. This seems like a test of what may well be on the horizon in terms of climate change and the extreme burdens it will place on (fragile) healthcare infrastructures.

What scholarship do you expect to arise from your project?

The focus is to provide a solid evidence base, or at the very least, to highlight where the voids and complexities lie in terms of climate change and health outcomes within the South African context. This has led to a number of side projects with the School of Psychology at Cardiff University, collaborating with French researchers under President Emmanuel Macron’s call to "make our planet great again", and, more recently, with the international collaborative initiative, Operation Wallacea.

This CE project is fundamentally transdisciplinary, as disciplinary silos cannot holistically or meaningfully tackle something as complex and multifaceted as climate change. As such, transdisciplinary programmes present challenges for universities to implement because of the compartmentalisation of academic fields. On the flip side, specialisation in key areas is also needed. I hope that the decoloniality movement in South Africa, Latin America, and also, more recently, in Europe, can help break down some of these academic silos which are very Cartesian in practice.

How are you and the team working on the project dealing with the coronavirus pandemic and the South African lockdown - how has this affected your project, or do you see this an opportunity to find new ways of working?

We have placed site visits on hold for the time being. The focus has been on generating an evidence base for climate change and health in South Africa, and advancing national policy. In terms of the parallels or synergism between climate change and the Covid-19 pandemic (apart from that which I have already drawn), the rapid global transformation in behavioural patterns due to the pandemic has proven that behaviour change can indeed happen in a short space of time - an ecological revolution can indeed still happen.

In addition, deforestation and environmental degradation have brought humans and animals into closer contact, thus making the risk of zoonotic viruses jumping to humans much more real. The Ebola outbreak was also indirectly linked to climate change where we witnessed how food insecurity, as a result of drought-induced crop failures, led people in such situations to consume bush meat.

* Compiled by Rivonia Naidu-Hoffmeester, Communications and Marketing Specialist, College of Human Sciences

Publish date: 2020-06-23 00:00:00.0

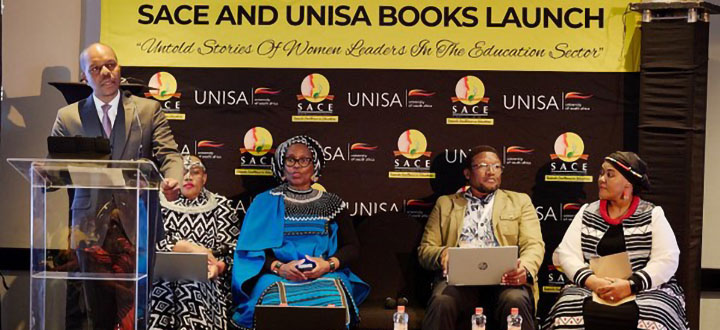

WiLM project culminates a vision for transformation in education

WiLM project culminates a vision for transformation in education

CAS students take centre stage in shaping academic quality and support

CAS students take centre stage in shaping academic quality and support

Unisa engaged scholarship project heads to parliament

Unisa engaged scholarship project heads to parliament

Unisa and ATUPA recognise researchers for ingenuity and innovation

Unisa and ATUPA recognise researchers for ingenuity and innovation

Recognising the unceasing resilience of women

Recognising the unceasing resilience of women