College of Human Sciences

Breaking ignorance about deafness and deaf education

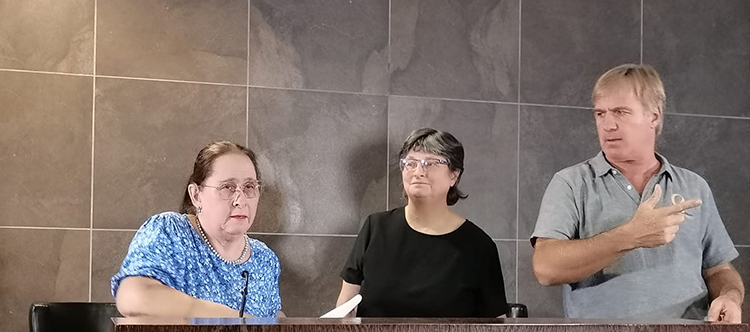

Karina Jooste-Van Aarde (left), being interviewed by Professor Ella Wehrmeyer (on her right) during the launch of her book entitled My child is deaf or hard of hearing – What now?. Next to them is Dirk Venter, a sign language interpreter.

On Friday, 1 April 2022, the Department of Linguistics and Modern Languages, in collaboration with the Unisa Language Unit at Unisa, launched a book titled My child is deaf or hard of hearing – What now? written by Karina Jooste-Van Aarde. Several guests from both the hearing and deaf communities were invited to the Bamboo Auditorium at Unisa’s Muckleneuk campus, and a larger audience joined virtually through MS Teams. The launch took the form of an educational session and an awareness drive to break the ignorance about deafness and deaf eduction to the community at large.

Karina Jooste-Van Aarde (left), Prof. Koliswa Moropa (right) from the Unisa Language Unit, Karin Koen (a BEd graduate who grew up completely deaf), her mother, Vera Koen (middle), and Professor Ella Wehrmeyer.

The book was birthed as a result of Jooste-Van Aarde’s 12 years of research and interest in deaf education and deaf matters, together with the Department of Linguistics and Modern Languages, as well as experience of her own upbringing and education as a deaf student/person. The book provides well-researched information and guidance to hearing parents who are raising deaf or hard-of-hearing children, but to also enlighten the hearing community usually ignorant of challenges facing the deaf.

About 90% of deaf and hard-of-hearing children have hearing parents, whereas only 10% of deaf and hard-of-hearing children have deaf parents. The realisation of hearing parents that their child is deaf brings shock, along with a lot of emotion and many questions. There is usually no proper parental guidance and since it is their first time dealing with deafness and problems associated with it, unfamiliarity and ignorance limit them in how to communicate with and teach their children.

Jooste-Van Aarde is a retired staff member of Unisa. She studied Linguistics for degree purposes at Unisa and worked in the Department of Linguistics and Modern Languages as a deaf co-researcher. She was a coordinator and diplomatic mediator between lecturers, postgraduate students and the deaf community. She also offered informal sign language classes at Unisa for students and lecturers.

“As a deaf person myself I am using my voice to make myself heard for the sake of the education of current and future deaf and hard-hearing children,” said Jooste-Van Aarde. She explained that an average deaf child in South Africa is neglected and very few parents make an effort to teach their deaf children spoken language. She said using both verbal and sign language concurrently bridges the gap between the hearing and the deaf.

Born with normal hearing, Jooste-Van Aarde became deaf in 1958 at just over two-and-a-half years old because of meningitis. Without no help or guidance in South Africa on deaf education and communication, her mother found her own way to efficiently teach and communicate with her daughter.

Asked what advice she could give parents, Jooste-Van Aarde said that it was important for deaf education to start with the parents at home because the first three years are most critical when it comes to language development. She explained that it was important to teach deaf children reading as young as 12 to 18 months and that while hearing children acquire language through hearing, deaf children acquire language through the eyes. In eliminating some of the misconceptions about deafness she said, “cochlear implants and hearing aids cannot turn a deaf child into a hearing child because deafness is permanent.”

Dr Fiona Ferris (right), a senior lecturer at the Department of Linguistics and Modern Languages, proudly holds her signed copy of the book entitled My child is deaf or hard of hearing – What now? Next to her is Karina Jooste-Van Aarde (left), the author.

Professor Ella Wehrmeyer from the North-West University, a former lecturer in the Department of Linguistics and Modern Languages at Unisa, worked with Jooste-Van Aarde as a co-researcher. Wehrmeyer’s research interests are more focused on corpus-driven sign language interpreting. Speaking at the launch, she said some of the fallacies that hearing communities typically have are thinking that sign language is the same as spoken language or that sign language is just waving arms and meaningless gestures. She said sign language has been proved to be a real language. She further explained that there are two types of sign language – a sign language which develops in the deaf communities as a natural language on the streets, and a type of sign language which mirrors spoken language with the purpose to train the deaf child to understand and use spoken language.

According to the Pan South African Language Board’s Sign Language Charter launched in 2020, South African Sign Language (SASL) is the primary language of deaf people in South Africa and should be respected as a language of choice to be used in all interactions. Professor Koliswa Moropa from the Unisa Language Unit acknowledged the pledges from the Charter that commit all people in South Africa to accept, recognise and respect the deaf person’s inherent right to use SASL. She acknowledged the contribution of Vera Koen and her completely deaf daughter Karin Koen (a BEd graduate), who demonstrated their real-life situation in their personal experiences with deafness difficulties. Moropa stressed the importance of creating platforms such as these where deaf people are not marginalised, but are given an opportunity to speak for themselves.

* By Neliswa Mzimba, Junior Lecturer (Translation Studies), Department of Linguistics and Modern Languages

Publish date: 2022-04-12 00:00:00.0

CAS students take centre stage in shaping academic quality and support

CAS students take centre stage in shaping academic quality and support

Unisa engaged scholarship project heads to parliament

Unisa engaged scholarship project heads to parliament

Unisa and ATUPA recognise researchers for ingenuity and innovation

Unisa and ATUPA recognise researchers for ingenuity and innovation

Recognising the unceasing resilience of women

Recognising the unceasing resilience of women

Unisa and SHECASA promote institutional health and safety

Unisa and SHECASA promote institutional health and safety