News & Events

Youth Day commemorations: a premature exercise?

Youth Day on June 16, commemorating the Soweto Uprising as it is popularly known, is a day set aside as a public holiday to commemorate the student uprising in South Africa represented mainly by student or learners in Soweto, which was initiated by young pre-tertiary learners who were revolting against an intended use of Afrikaans as a medium of instruction.

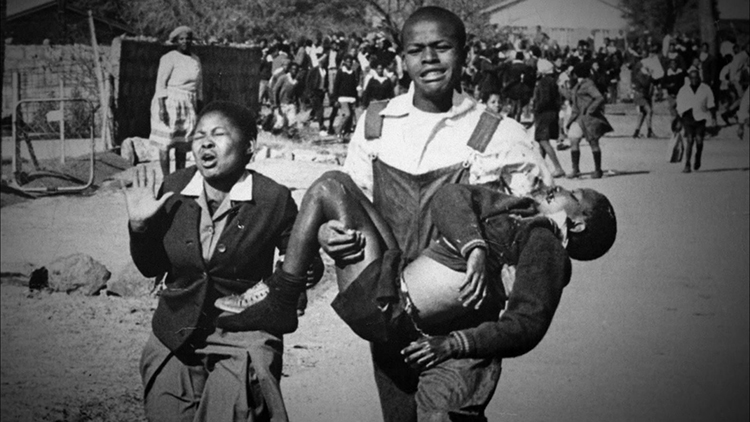

The iconic image of Hector Pieterson’s body being carried by a fellow student. Aged 13, he was one the first students to be killed during the 1976 Student Uprising in Soweto.

Tsietsi Mashinini, who was one of the leaders of this historic protest, in interviews on November 15, 1976 and March 14, 1977, respectively, says, ‘But in some way or another the students understands and identifies all elements of oppression like this Afrikaans thing – that is, our education, which simply is meant to domesticate you to be a better tool for the white man when you go and join the working community.’

These sentiments, in my view, are enough to dispel any notion that the Soweto Uprising was only focused on opposing Afrikaans as a medium of instruction. When Mashinini’s sentiments are absorbed and well-processed in one’s mind, it is vividly clear that the question of black youth participation in spaces of economy, be they spaces at a workplace or any other spaces of influence, was central and vital in his mind when he constructed this sentiment. Perhaps we can now look at it this way: 1976 youth was rising on the quality of their education, with focus to the role it was preparing them for in the economy market.

I argue that, because the cause has not yet been accomplished, commemorations or celebrations are premature. Besides that, the youth struggle, in so far as it relates to my understanding of the Soweto Uprising is concerned, has not yet been accomplished; some if not many gains of youth revolution, have been reversed – this also serves for the free education that is not necessarily free attained recently.

To this day, youth unemployment is on a consistent rise and seems to be met with unsustainable propositions. I hold the conviction that this has a strong relationship with the historic position of institutions of higher learning that produce such unemployable graduandi rather than the scarcity of job opportunities. It is almost impossible that while job opportunities are scarce, somehow that changes when a graduate is from Wits, the University of Cape Town, the University of Pretoria or Stellenbosch University (to mention some of the predominantly white universities), as opposed to when a graduate is from the Durban University of Technology, the Cape Peninsula University of Technology, the Walter Sisulu University and the Tshwane University of Technology.

It should also be considered that the adherence of the latter institutions to the cause of transformation could be one of the factors contributing to the vindictive treatment doled out to its alumni, as graduates from these ‘bush’ or ‘revolutionary’ campuses may well be at the receiving end of subtle punishment by captains of industry who have red-circled them as problem children that are most likely to polarise labour relations once hired.

If we follow Mashinini’s sentiments on what the ‘then’ education system sought to prepare black youth for, then the production belt of the current education system (if it is entirely different to the 1976 system), still channels the black graduandi to the same destiny as what 1976 generation was fighting to disrupt .

To date, participation and ultimate take-over by black young people in spaces of authority and taking control of the economic sector and other strategic spaces of the society remains a pipe dream.

We must be cognisant of the key factor that youth is nothing but a passing phase. Our limited appreciation of the fact that it is natural that one would be a catalyst of youth take-over, ultimately would mean that it is possible that only the subsequent generations would enjoy benefits of such an assignment and those who would have advocated for such a change shall live to see their cause working against their interest.

This should show us that, until we have youth advocates, loyal to the cause of youth take-over, the struggle shall continue. Here the present-day youth is not only disadvantaged by the quality of education it received; but it is also confronted by a broad fight of taking over from its own predecessors. The exclusion of young people shall persist. Having quotas of as how many members of provincial and national assembly and even MECs, and ministers and deputy ministers is not a conclusive end to a pervasive challenge of youth unemployment and lack of economic opportunities. The country is more than ever on a mode of producing an army of poor youth and this should no longer be a concern but a national calamity that needs to be attended to. We need to strive have one type of youth as opposed to the three-fold typology youth we currently have, that is, youth in school or active in the economy, youth out of school and the youth in conflict with the law.

If we now appreciate that the cause as identified by the 1976 youth has not been achieved, we should agree that the commemoration of such a cause is premature. We have nothing to celebrate because the battle is still on. If there was ever a time to realise that we are at the peak of youth revolution, it is now.

As these commemoration celebrations were taking place in June this year, I could not help but wonder, ‘could it be sensible that, while other students were on what is now called the Hastings Ndlovu bridge, from Orlando East to Orlando West, confronted with brutal police force, others were commemorating that cause already at the Orlando Stadium? Would it be the right time? Is it the right time, now?’

* By Sifundo kaZolile Ndzube

|

About the author Sifundo Zolile Ndzube hails from Nqamakwe in the Eastern Cape. He received junior education in the junior secondary school in his village, and later went to Gauteng to receive senior secondary schooling. Sifundo served in both the RCL and COSAS during his pre-tertiary schooling, and is currently serving as the Western Cape Unisa RSRC chairperson. Sifundo is the former Youth and Agriculture and Rural Development Municipal Chairperson in the Mnquma Local Municipality. |

Publish date: 2020-08-11 00:00:00.0