News & Media

‘There is something wrong with the wiring in our heads,’ argues Mosibudi Mangena

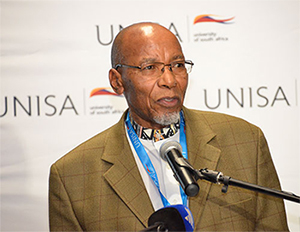

Dr Mosibudi Mangena (former Minister of Science and Technology and former President of the Azanian People’s Organisation) delivered the eighth Unisa Annual Memorial Lecture in honour of the late Professor Es’kia Mphahlele.

Dr Mosibudi Mangena, former Minister of Science and Technology and former President of the Azanian People’s Organisation (AZAPO), was in his element when he delivered the eighth Unisa Annual Memorial Lecture in honour of the late Prof Es’kia Mphahlele.

The lecture, taking place on the occasion of the official launch of the new Unisa Student Centre in Polokwane on 29 September 2017 was exploring the theme Developing a decolonised consciousness. And, being a long-standing and vociferous proponent of black consciousness, Mangena was not just equal to the task; but miles beyond it.

At the outset, and though modestly so, he put beyond doubt his qualification to deliver homage to Es’kia Mphahlele, one of the finest teachers and writers ever produced by South Africa and Africa and whom he aptly referred to as ‘a colossus in the fields of literature, philosophy, the arts and education’. This is demonstrated by his visits to Mphahlele’s home in Lebowakgomo when he was still alive and after his retirement from teaching. During these visits, they would spend time in his study, surrounded by rows and rows of books and talk and talk.

Mangena also reminisced about his observation of the old man Mphahlele around children during reading campaigns in Gauteng. It is here that his love for the written word would truly reveal itself. Such occasions, as Mangena puts it, ‘would bring a twinkle in his eye’.

As he zeroed in on the topic of the day, he intimated that, had Mphahlele been alive today, he would be ‘positively intrigued and energised by some of the demands by our youths for a decolonised education’. After all, Mphahlele was known to have been aggrieved by the absence of African culture in the planning of our education system, lamenting the fact that education in South Africa and in most other parts of Africa, was alienating and seeking to take us further and further away from who we are.

Unisa academics Prof Sabelo Gatsheni-Ndlovu and Prof Kealeboga Maphunye were part of a panel discussion at the lecture.

A well-travelled man, who stayed and taught in Ghana and Nigeria and in countries such as Finland, Germany, Denmark, France, Sweden and the USA, Mphahlele did not mince his words about how he experienced these countries. He is known to have proclaimed that working in Ghana and Nigeria gave him back his Africa, while the systems in the latter countries reminded him that he was an African.

Mangena lamented the same state of affairs with the South Africa of today. If you don’t know that you are black, he says, ‘the school, the campus, the lecture room, the bank, the insurance company, and the world of work will remind you of that fact. Going into most restaurants, airports, or bookshops does not feel like you are in a country where the vast majority of the population are black, and only the township, village, taxi rank, the bus stop, or the train station would tell you that,’ he added.

Mangena places the blame for many of the problems of the black majority squarely at the doorstep of the same black majority. According to him, many of these things are happening because ‘there is something wrong with the wiring in our heads, especially the heads of the black intelligentsia’.

‘As a result of the colonially-modelled and inspired education we have received, our minds are hobbled so much that we cannot do anything that does not answer to that education; and we seem incapable of imagining and engineering an education system that is substantially different from our colonially-conceived education,’ he argued.

He further presented the counter-argument that whites, on the contrary, are wired differently and are not confused about who they are and what they want. Hence, when a white child is born and it’s a boy, he would not be named Matome van der Merwe, but Piet van der Merwe. Similarly, if it’s a girl, she would be Zelda van der Merwe, and not Mokgadi van der Merwe. Four hundred years of being in Africa had not made them forget who they are.

‘There is no debate. They just know. That’s how they are wired. They just know that their children will speak their language at home, would recite their rhymes at crèche, would learn their language at school, and read books written by their authors. They just know,’ said Mangena.

In contrast, black people would do the opposite, according to Mangena. Though most would not even have been to Europe, they would still name their son Piet and their daughter Claudia, at times not even knowing what these names meant.

He lamented that fact that at times ‘we would put other people’s hair on our heads even if we don’t know what diseases they might have suffered from or whether the owners of the hair are dead or alive. As long as the hair is straight and resembles that of the colonialists, it’s okay, we love it. That’s the way we are wired. On the other hand, whites would not be seen dead with an Afro-wig on their heads. That’s just how they are wired. They just know that the Afro-wig is not for them’.

He said that blacks would be enthusiastic about their children reciting nursery rhymes in a colonial language, even if the poor children don’t understand. He said that they don’t realise that, in that process, they are putting up formidable barriers to the learning of their own children.

Mangena made a similar argument in relation to the concept of marriage. He argued that somehow, blacks are suffering from the illusion that their marriages are not complete unless they include the colonial version of matrimony in them. ‘So, we do the same thing twice. We do lobola and then go and buy rings, wear a white veil and a suit, get blessings in church, and only then do we feel properly married’, he lamented.

In the final analysis, Mangena urged blacks to embark on a deliberate process of dismantling the wiring in their heads and re-wire themselves anew.

‘The new and proper wiring of our heads should be loaded with software that would drastically diminish our excessive love for our former colonialists, their language, culture, and other such attributes,’ he said.

He argued that we seem to confuse the language of the colonialists with intelligence and skills, whereas the most critical things are the concepts, not the language. He urged black people to take a leaf from the Japanese and the Koreans, Germans and Italians, whose engineers and technicians are excelling while using their own languages. Or even draw lessons from the Indonesians, who, at independence, banned Dutch as an official language and adopted a standardised form of Malay as their official language.

‘Why is it necessary for our people to learn a colonial language before they can learn carpentry, plumbing, bricklaying, welding, painting, electricity, motor mechanics, agriculture and similar skills?

Mangena’s answer to this is simple. He argued that for this to come to pass, blacks must first re-wire their heads so that, for the most part, they just know.

Zandile Sodladla (Unisa SRC President) was also part of the panel discussion. |

Dumisani Hlophe (School of Governance at Unisa) was the moderator of the panel discussion. |

The lecture concluded with a panel discussion and reflection by Unisa academics, Prof Sabelo Gatsheni-Ndlovu and Prof Kealeboga Maphunye as well as the President of the Unisa Student Representative Council (SRC), Zandile Sodladla. The discussion was moderated by Dumisani Hlophe, from the School of Governance at Unisa.

Click here for Dr Mosibudi Mangena’s full address from the lecture.

*By Martin Ramotshela

Publish date: 2017-10-03 00:00:00.0

Community champion and agricultural entrepreneur extraordinaire honoured by Unisa

Community champion and agricultural entrepreneur extraordinaire honoured by Unisa

Ghanaian-born Swede earns PhD in Information Sciences from Unisa

Ghanaian-born Swede earns PhD in Information Sciences from Unisa

Unisa awards honorary doctorate to exemplary philanthropist and entrepreneur Collen Tshifhiwa Mashawana

Unisa awards honorary doctorate to exemplary philanthropist and entrepreneur Collen Tshifhiwa Mashawana

Inhlanyelo Hub explores financing and sustainability at the International Conference on Business Incubation

Inhlanyelo Hub explores financing and sustainability at the International Conference on Business Incubation

Unisa remains anchored among the waves

Unisa remains anchored among the waves